Latest Posts from William D. Finlayson

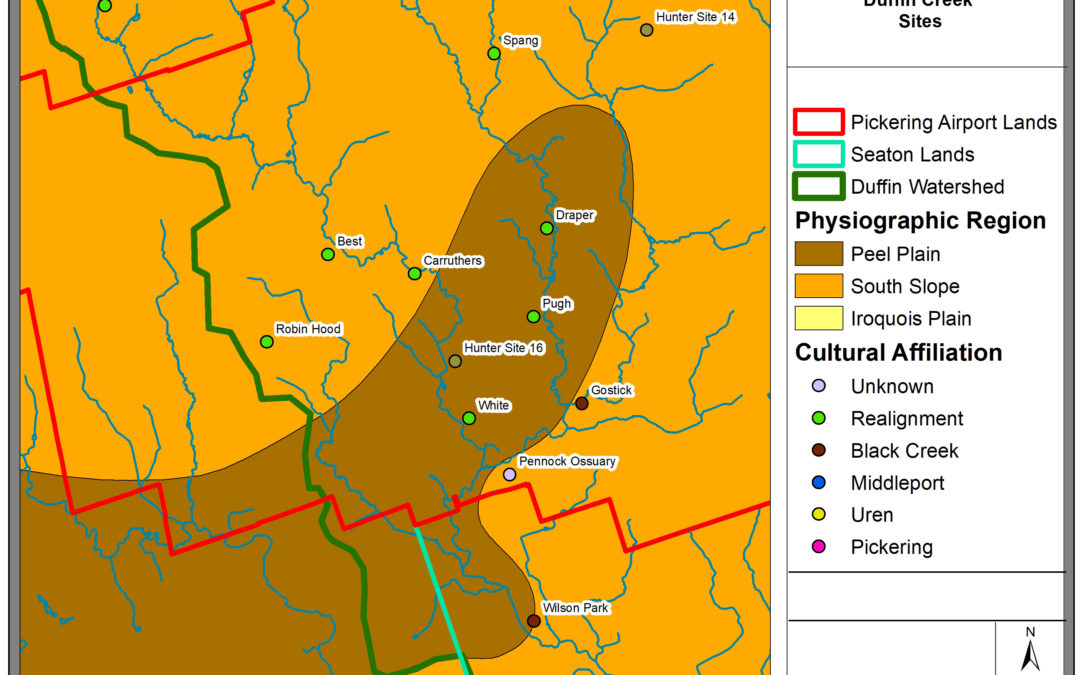

The White Site

Tripp noted 10 characteristics which suggested that the White site was a farm hamlet, occupied seasonally over many years. Among these unusual features were an absence of village planning and defensive planning in the placement of houses, which on the other hand was so prevalent at Draper.

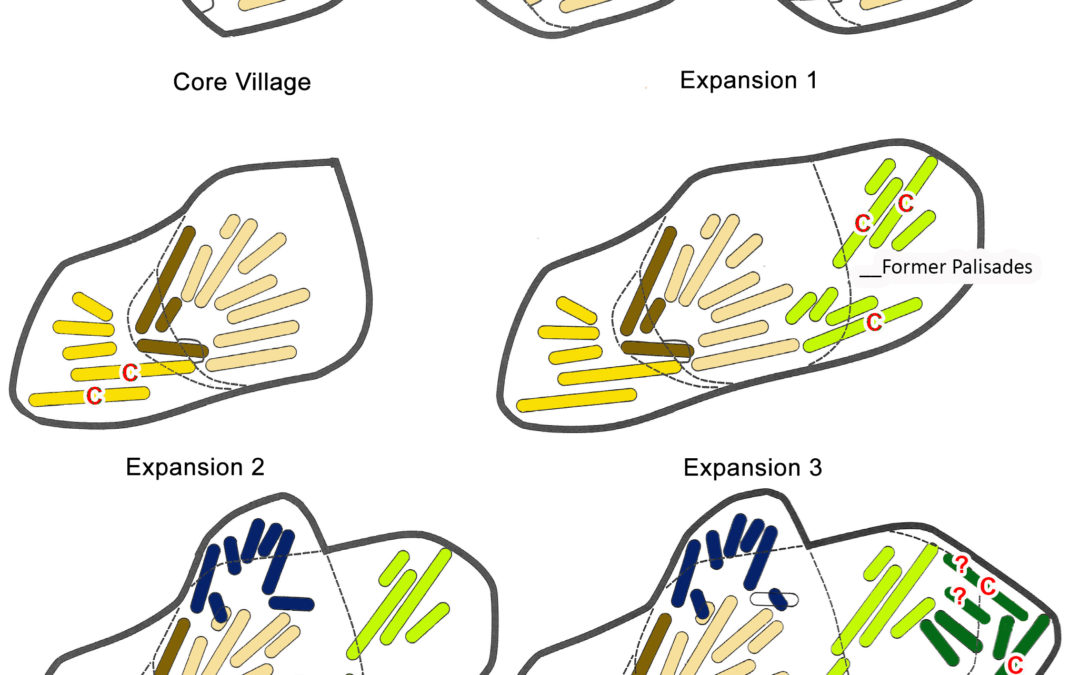

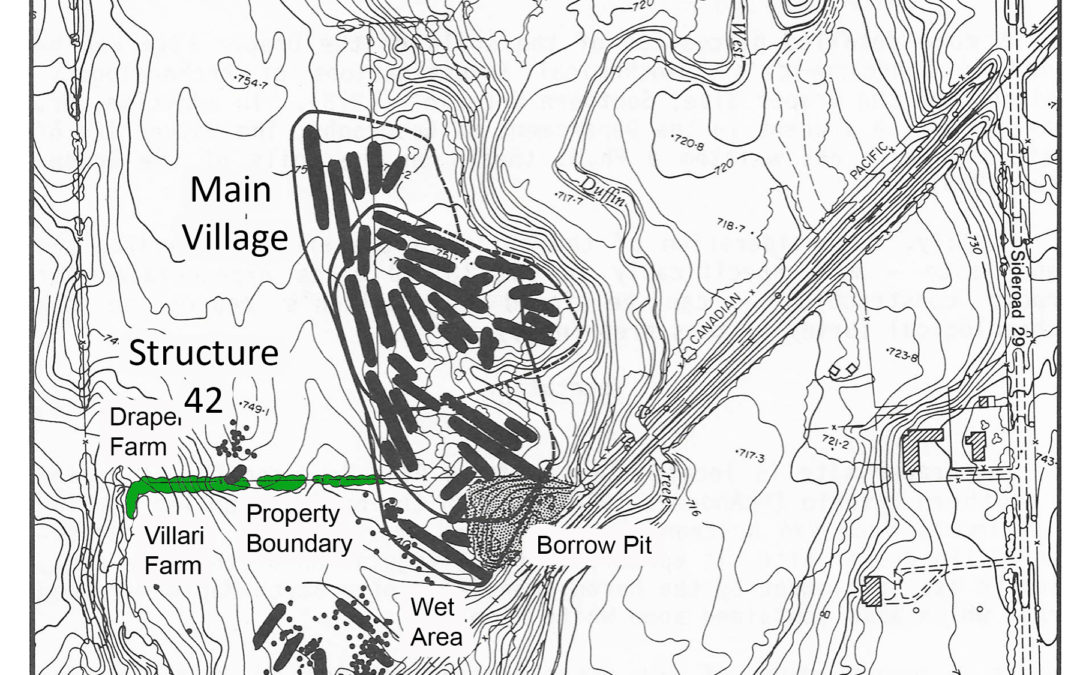

The Draper Site: Special Structures, Chiefs’ Houses

We know from the historical documents of the Historic Huron that these types of houses existed. We can use this data to help us better understand the occupants of the Draper site. It is noteworthy that as the village expanded, these long longhouses were situated on the outer edges of the expanded part of the village. Such a pattern of placement of chiefs’ houses—to potentially assist in village defenses—may be unique to the Draper site.

The Draper Site: Special Structures, Visitors’ Houses

One of the most intriguing aspects of the Draper Site was that it began as a typical small community of about 8 longhouses in a palisaded village, 1.2 hectares in size. Amazingly, it expanded five times to become a 3.4-hectare village comprised of 39 houses, most of which were occupied at the same time, with an estimated population of 1,800 people. Also, quite interesting was that not all of the structures we discovered were longhouses. There were three which I believe were unique structures used to house visitors to the Draper village. We know from historical documents written by early explorers and missionaries…

The Windmill Site

We discovered a second location we called The Windmill Site, inspired by an old windmill still standing beside the site. We also found the cellars of both of these homes which can be seen in the aerial picture taken by our drone. There were thousands of artifacts dating back to the late 19th and early 20th century, most of which were metal. We collected a few as representative samples of the kinds of artifacts in use at the turn of the century.

The Yake Site

This is the first archaeological site we have excavated that was occupied by tenants. The investigation reminded me of the tremendous variability of 19th century homesteads and farmsteads. It seems that every site is slightly different, and each one provides additional insights into life as it was more than a century and a half ago. Interestingly at times, these insights can be very different than the written history of the era.

Setting the Stage for the Yake and Windmill Sites, Two 19th Century Farmsteads in Whitchurch-Stouffville Township, Ontario

It’s truly amazing, the coincidence of excavating two 19th century farmsteads located in the agricultural fields of the Indigenous people who occupied the Mantle site (many of whom probably occupied the Draper site as well), while at the same time I’ve been actively reviewing our excavations at Draper from more than 40 years ago. One of the wonderful aspects of my work is that we never know where we will be working and what we are going to find.

Revitalizing Wilfrid Jury’s Museum of Indian Archaeology and Pioneer Life – Phase 1

The first phase in revitalizing Wilfrid Jury’s museum involved changing reporting responsibility for the museum as a non-academic unit of The University of Western Ontario … With the appropriate research and exploration, we decided to establish the museum as a UWO research centre which would accomplish what we had learned through Professor Ames, in that it would be a separate company with its own charitable registration.

Wilfrid Jury’s Museum of Indian Archaeology and Pioneer Life in 1976

This was state of affairs at the museum at that time. I assumed the position of Executive Director in February 1976 and began the challenge of its revitalization as an archaeological research centre committed to field work, analysis, and reporting of sites in southwestern and southcentral Ontario. It was a daunting task, but one which was rewarding and productive for more than 20 years.

My Early Years at The University of Western Ontario

It was with this background knowledge that I took on the job to dig the Draper site, which was a vital component in the revitalization of Wilfrid’s Museum, in part because it demonstrated the ability of archaeology to continue to attract large contracts to the university. It is also part of the narrative in understanding how the opportunity arose for me to become Executive Director of the Museum without a university salary.

Draper Site Excavations – Trials and Tribulations

One of the challenges in undertaking the excavations at the Draper site in 1975 and 1978 was ensuring the safe operation of the dig, the security of the excavations, and providing accommodations and meals for our crews which at times numbered up to 60 people. These are just a few of the more memorable events at Draper, which remind me of the challenges of directing the size of crews we needed to complete the largest and most significant excavations of an Iroquoian village ever undertaken in the province. Still, one of the highlights of my career I feel fortunate to share and contribute to our archaeological history.