As we continue this sensitive topic from Evidence for Indigenous Warfare at the Draper Village Site Part 1, we reiterate that although this isn’t an easy part of any country’s history to explore, let alone read about or appreciate, it does help to understand the past in a way that gives clarity to the present and future generations of its people.

Please note as before, some of this post includes graphic details which may be uncomfortable for some readers.

In this blog, Part 2, we address the scattered fragments of human bone recovered from the many houses and middens across the Draper site—clearly indicative of warfare. Historical documents for the Huron-Wendat from the 17th century document the torture of prisoners as a practice associated with endemic warfare and one of the characteristics of Iroquoian societies in Ontario during the Late Woodland period (circa A.D. 800-1650).

According to these historical records:

Warfare for the Iroquoians involved ongoing raids between villages which had been attacked by war parties from other villages. If one or more individuals from a village were killed or captured by a war party, this would result in a retaliatory raid from that village to avenge the killing or capture of its people. We believe that the purpose of such widespread warfare was not to destroy the enemy or his village, but to provide a means for men to demonstrate their bravery.

If individuals were captured in one of these retaliatory raids, sometimes they were killed immediately. Other times they were returned to the attacker’s village where some were adopted into the captors’ village while others were tortured. Part of the torturing of captives was a belief that if a captive was brave during torture, parts of his body could be eaten in a form of ritualistic cannibalism, the belief being that consuming his flesh would result in this individual’s bravery being transferred to the person who consumed his flesh.

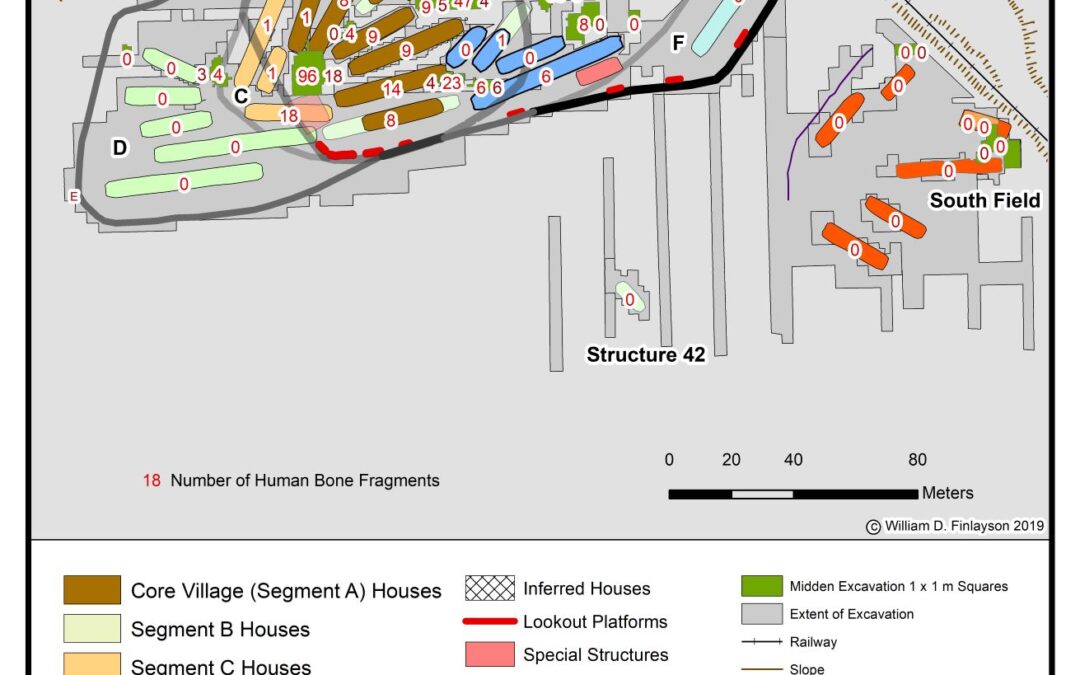

At the Draper site, we recovered 377 fragments of human bone from the middens and houses we investigated. Their distribution is illustrated above in Figure 1. We believe that some of these fragments of broken human bone are indicative of ritual cannibalism which may have involved breaking open the long bones to get the edible marrow inside.

This interpretation of the human bone fragments recovered from the Draper site relies, in part, on analogies with the historic Huron-Wendat who occupied what is today Simcoe County in the 16th and 17th centuries. I believe such comparisons are valid even though current research suggests that Draper and its successor villages, Spang and Mantle, were not occupied by Huron-Wendat, but another group of Iroquoians who inhabited the Duffin Creek at the same time as the Huron-Wendat occupied Simcoe County.

The more research we do into the Late Woodland occupation of southern Ontario by Iroquoian and Anishinabek peoples, the more we realize how little we know and how much more can be learned. This requires rethinking traditional, widely accepted perspectives and interpretations and re-analyzing extant collections of artifacts and debris with an open mind. It also requires the incorporation of the new information which is available on Anishinabek oral histories, and a consideration of all available archaeological data not just that recovered by selected archaeological consulting firms.

Thank you as always for following this work. We are committed to searching for the truth, whether it be in Indigenous history or Euro-Canadian history of the 19th century Ontario.

Respectfully yours,

Bill

William D. Finlayson, Midland, Ontario

Ontario’s Leading and Senior-Most Archaeologist and Author

Founder of Our Lands Speak Book Series and Occasional Papers in Ontario Archaeology

Feature image: Figure 1, Distribution of Human Bone Fragments at the Draper Site

All rights reserved. The use of any part of this publication reproduced, transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, or stored in a retrieval system, without the prior written consent of the author and publisher is an infringement of the copyright law. To that end, every attempt has been made to give proper acknowledgement, and access appropriate permissions for quotes. Any oversights are purely unintentional. In the unlikely event something has been missed, please accept our regret and apology, and contact us immediately so we can investigate and rectify as needed. All of the quantitative factual information is recorded in various published and unpublished sources and can be provided upon request.