Latest Posts from William D. Finlayson

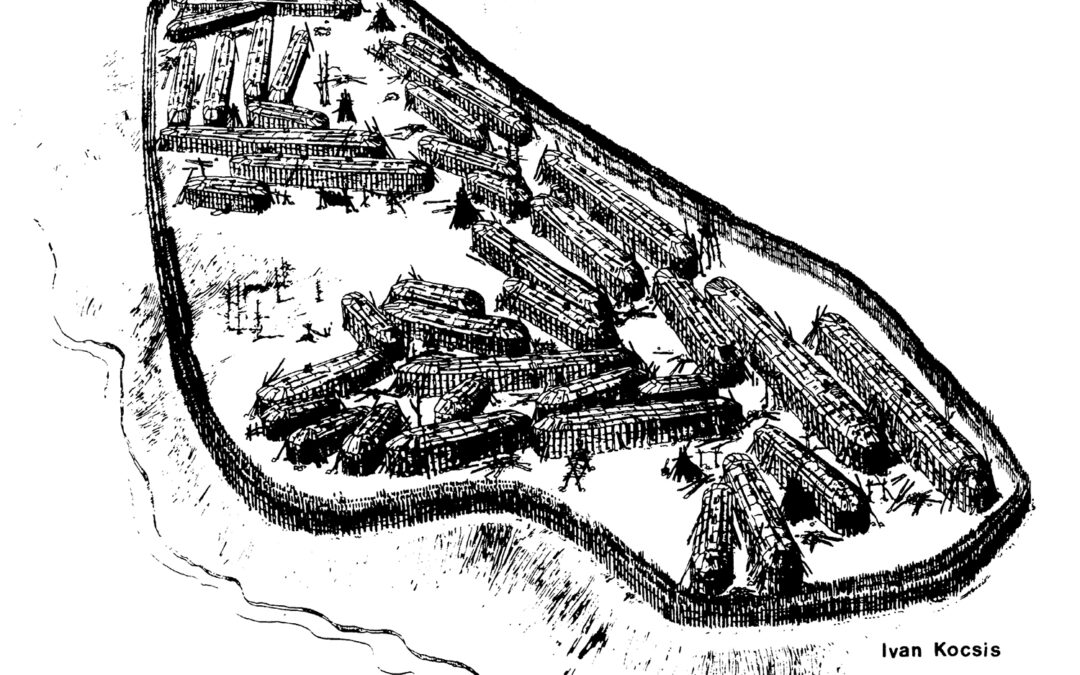

An Artist’s Concept of the Draper Site

The almost complete excavation of the Draper site represents one of the first and certainly the largest of a Late Woodland village in south-central Ontario investigated on a salvage archaeology basis. I saw our work at Draper as an opportunity to have Ivan Kocsis, a very talented artist in Hamilton, create an artist’s conception of what the Draper site might have looked like after expanding five times to become a very large village of almost 2,000 people. This illustration has generally been very well received and has been used, with permission and proper acknowledgement, in a relatively large number of textbooks on archaeology.

The Draper Site Endorsed by James W. Bradley, Ph.D., Director Emeritus of Robert S. Peabody Museum of Archaeology

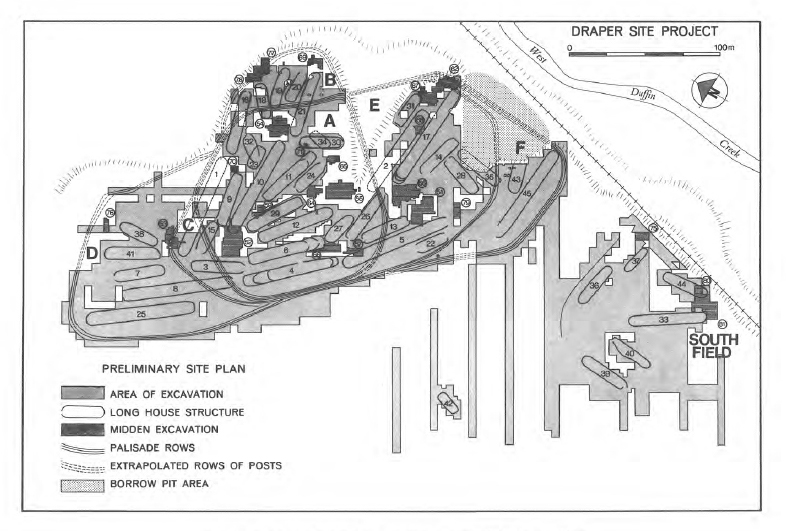

I am tremendously proud to announce the publication of “The Draper Site, an Ontario Woodland Tradition Frontier Coalescent Village in Southern Ontario, Canada: Looking Back, Moving Forward,” the fifth volume in Our Lands Speak series and what I believe is a groundbreaking study. I reviewed more than forty publications, theses, articles, and unpublished reports as a prelude to the reconsideration of some of the key aspects of the Draper site. Draper is used to define a specialized type of coalescent village, the Frontier Coalescent Village. This study provides new insights into the coalescence of at least five smaller villages, some from Duffin Creek and some from further afield at Draper, and the special mechanisms which made this possible and sustainable.

Early Engagement with Indigenous People

This early program of incorporating Huron-Wendat students from Wendake, Quebec was one of the first examples of sharing the process of archaeological investigations with 20th century Indigenous peoples. One of the fondest memories I have of this pioneering program was being presented with a smoking pipe and stone bowl and a wooden stem made and signed by Regent Sioui for my role in facilitating this program. We continue to look back to move forward.

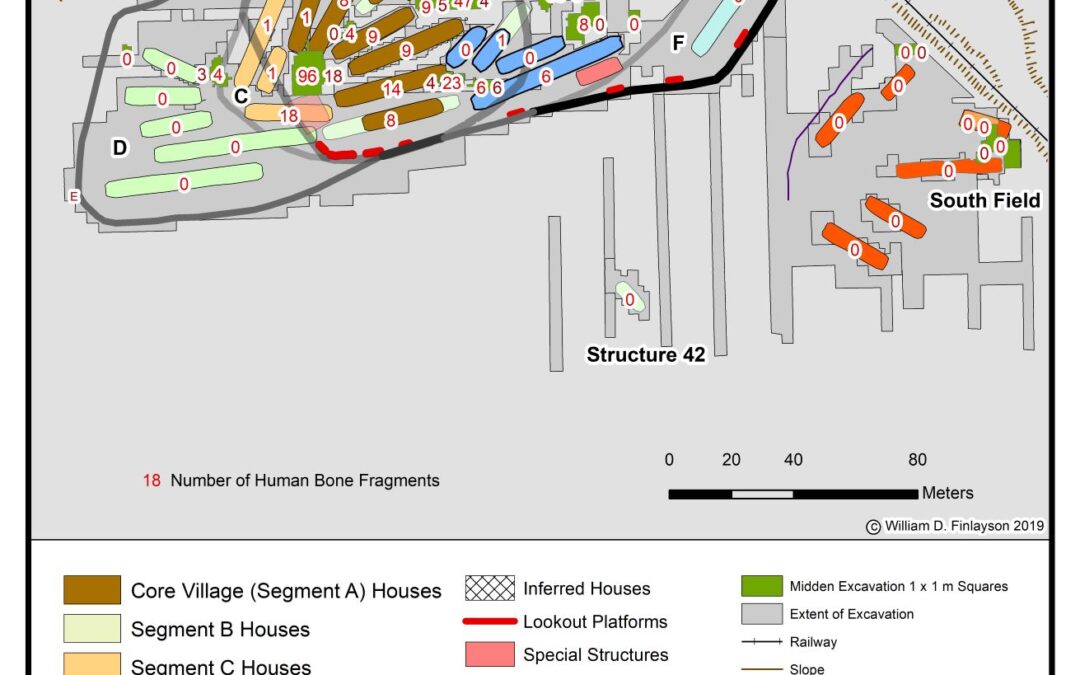

Evidence for Indigenous Warfare at the Draper Village Site Part 2

As we continue this sensitive topic from Evidence for Indigenous Warfare at the Draper Village Site Part 1, we reiterate that although this isn’t an easy part of any country’s history to explore, let alone read about or appreciate, it does help to understand the past in a way that gives clarity to the present and future generations of its people. The more research we do into the Late Woodland occupation of southern Ontario by Iroquoian and Anishinabek peoples, the more we realize how little we know and how much more can be learned.

Evidence for Indigenous Warfare at the Draper Village Site Part 1

This isn’t an easy part of any country’s history to explore let alone read about or appreciate, however, it does help to understand the past in a way that gives clarity to the present and future generations of its people. As archaeologists, we don’t always know what we’re going to come across in our work. As such, we take great care and respect in excavating and preserving our findings. Some of our evaluations may be considered professional interpretations due to missing data, yet others present with such clear fact as indicated here that there is no other side but a single truth. Please note: part of this post contains graphic details which may be uncomfortable for some readers.

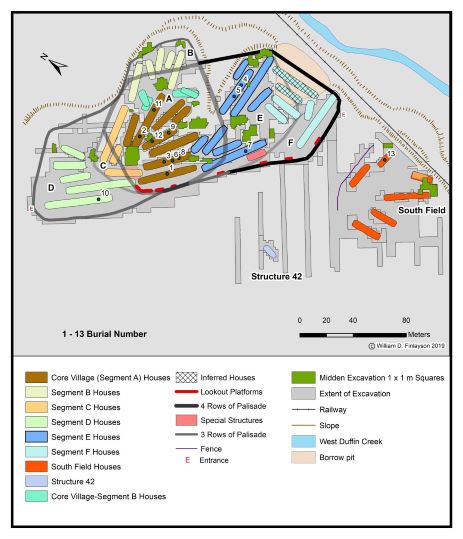

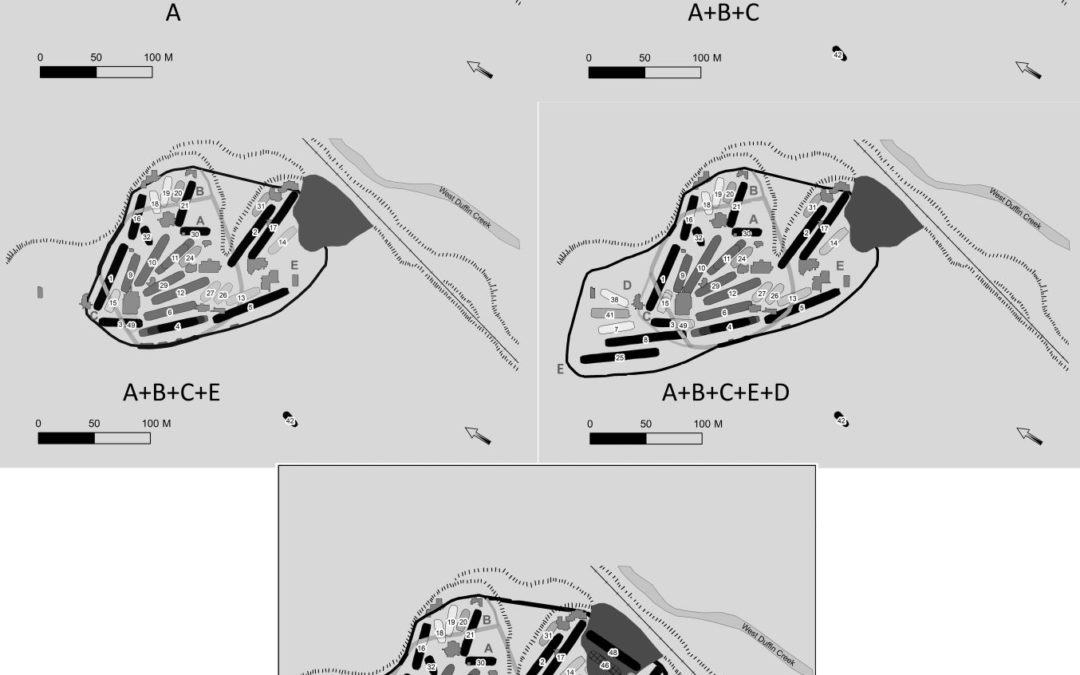

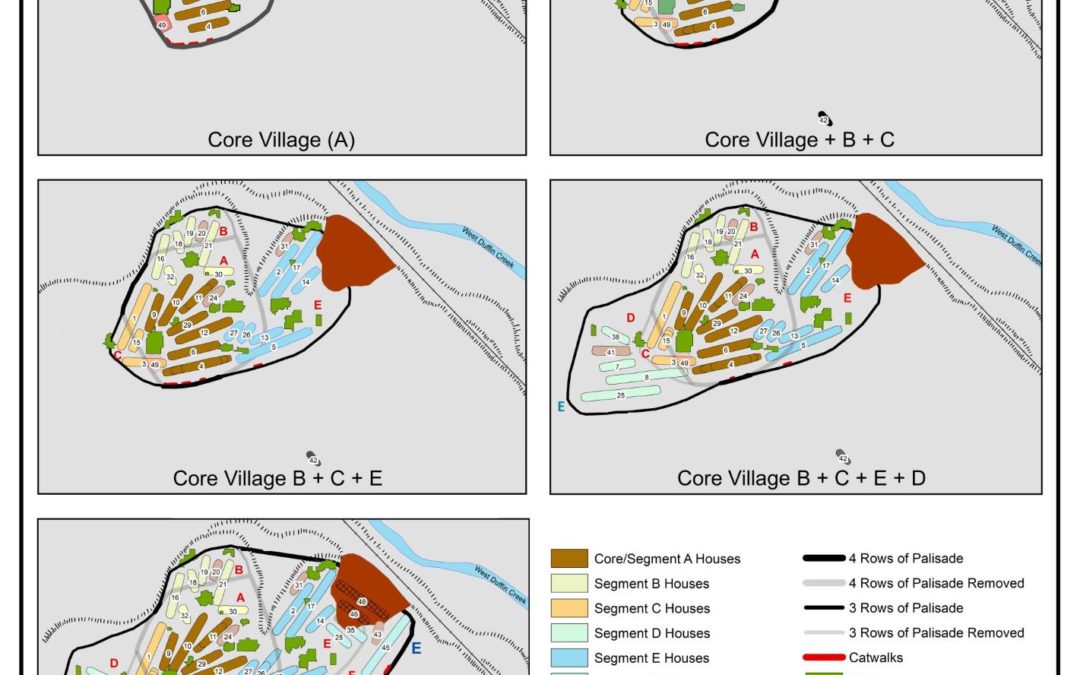

Draper Village Site Defensive Structures Part 2

Here, we look at the additional planning that the Iroquoians—who lived at Draper and who moved into Draper—undertook as the various expansions of the village were constructed. As you will see, there was significant planning and I believe that much of this was of a strategic nature. Its specific purpose was to position longhouses to provide additional defensive barriers to assist in the protection of the village . . .

Draper Site Village Defensive Structures Part 1

Conrad Heidenreich, a geographer who wrote extensively on the Huron, provides in his 1970 book Huronia a description of one palisade from one village. The following was written by the French explorer Samuel de Champlain during his visit to Huron County in 1615-1616: “Fortified by wooden palisades in three tiers, interlaced into one another, on top of which, they have galleries which they furnish with stones for hurling, and water to extinguish the fire that their enemies might lay against their palisades.”

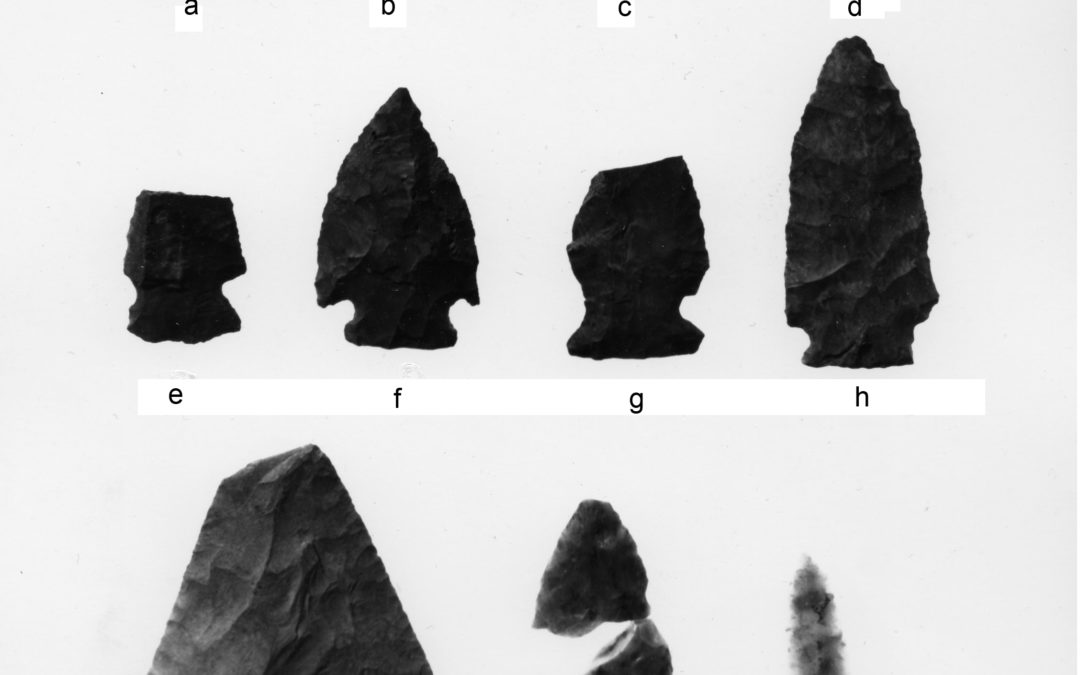

Iroquoian Arrowhead Collectors at the 16th Century Draper Site

One never knows what unusual artifacts are to be found in the collections at sites such as Draper and what new insights will result from their study.

Fittingly, I continue this blog series with another extraordinary set of findings we recovered from our excavations at the Draper site in 1975 and 1978. This involves 10 projectile points which predate the occupation of the Draper Village by many centuries. Indeed, one of these projectile points may be 8,000 to 8,900 years old, while some are several millennia old.

Neutral Indigenous Peoples Living at the Draper Site

At Draper, almost 98% of the chert used to make arrow points, scraping tools, and other cutting and scraping instruments were made from Onondaga chert. This chert was found along the north shore of Lake Erie in an area occupied and probably controlled by the Neutral. More recent research on Draper has revealed that there are other artifacts characteristic of the Neutral People. One of these was a bead made from the toe bone of a deer.

The Draper South Field

We discovered 7 houses about 40 metres south of the Draper Main Village. Two of these houses overlapped, with one being shorter. I believe the latter may have been lived in by the workers who built the rest of the houses. There was eventually a total of 6 houses separated from the Main Village by a fence, and likely occupied at the same time.